Marie Delphine Macarty or MacCarthy (March 19, 1787 – December 7, 1849), more widely known as Madame Blanque, until her third marriage, when she became known as Madame Lalaurie, was a New Orleans Creole socialite and serial killer who tortured and murdered slaves in her household.

Born during the Spanish colonial period, Delphine Macarty married three times in Louisiana, and was twice widowed. She maintained her position in New Orleans society until April 10, 1834, when rescuers responding to a fire at her Royal Street mansion discovered bound slaves in her attic who showed evidence of cruel, violent abuse over a long period. Lalaurie's house was then sacked by an outraged mob of New Orleans citizens. She escaped to France with her family.

The mansion where Lalaurie lived is a landmark in the French Quarter, because of its history and its architectural significance. It is located at 1140 Royal Street.

Marie Delphine Macarty was born in New Orleans on March 19, 1787, as one of five children. Her father was Louis Barthelemy de McCarty (originally Chevalier de MacCarthy), whose father Barthelemy (de) MacCarthy brought the family to New Orleans from Ireland around 1730, during the French colonial period. (The Irish surname MacCarthy was shortened to Macarty or de Macarty.) Her mother was Marie-Jeanne L'Érable, also known as "the widow Le Comte", as her marriage to Louis B. Macarty was her second. Both were prominent in the town's European Creole community.

On June 11, 1800, Marie Delphine Macarty married Don Ramón de Lopez y Angulo, a high-ranking Spanish royal officer, at the Saint Louis Cathedral in New Orleans.

In June 1808, Delphine married Jean Blanque, a prominent banker, merchant, lawyer, and legislator. At the time of the marriage, Blanque purchased a house at 409 Royal Street in New Orleans for the family, which became known later as the Villa Blanque. Delphine had four children by Blanque:

• Marie Louise Pauline

• Louise Marie Laure

• Marie Louise Jeanne

• Jeanne Pierre Paulin Blanque

On June 25, 1825, Delphine married her third husband, physician Leonard Louis Nicolas Lalaurie, who was much younger than she. In 1831, she bought property at 1140 Royal Street, which she managed in her own name with little involvement of her husband. In 1832 she had a 2-story mansion built there, complete with attached slave quarters. She lived there with her third husband and two of her daughters, and maintained a central position in New Orleans society.

The Lalauries kept several black slaves in slave quarters, attached to the Royal Street mansion. Accounts of Delphine Lalaurie's treatment of them between 1831 and 1834 vary. Harriet Martineau, writing in 1838 and recounting tales told to her by New Orleans residents during her 1836 visit, claimed Lalaurie's slaves were "singularly haggard and wretched;" however, in public appearances Lalaurie was seen to be generally polite to black people and concerned with her slaves' health. Court records showed that she manumitted (freed) two of her slaves (Jean Louis in 1819 and Devince in 1832). Martineau wrote that public rumors about Lalaurie's mistreatment of her slaves were so widespread that a local lawyer was sent to Royal Street to remind Lalaurie of the laws for the upkeep of slaves. During this visit, the lawyer supposedly found no evidence of wrongdoing or mistreatment of slaves by Lalaurie.

Martineau also recounted other tales of Lalaurie's cruelty that circulated among New Orleans residents around 1836. She said that, after the visit of the local lawyer, one of Lalaurie's neighbors saw one of the Lalauries' slaves, a twelve-year-old girl named Lia (or Leah), fall to her death from the roof of the Royal Street mansion while trying to escape punishment from a whip-wielding Delphine Lalaurie. Lia had been brushing Delphine's hair when she hit a snag, enraging Delphine, who promptly grabbed the whip and chased her. Her body was buried on the mansion grounds. According to Martineau, this led to an investigation of the Lalauries, in which they were found guilty of illegal cruelty and forced to forfeit nine slaves. They were bought back by the Lalauries through an intermediary relative, and returned to the Royal Street residence. Similarly, Martineau recounted stories that Lalaurie kept her cook chained to the kitchen stove, and beat her daughters if they attempted to feed the slaves.

On April 10, 1834, a fire broke out in the Lalaurie residence, starting in the kitchen. When police and fire marshals got there, they found the cook, a seventy-year-old woman, chained to the stove by her ankle. She later said she'd set the fire as a suicide attempt because she feared being punished. She said that slaves taken to the uppermost room of the mansion never came back. As reported in the New Orleans Bee of April 11, 1834, bystanders responding to the fire attempted to enter the slave quarters to ensure that everyone had been safely evacuated. Upon being refused the keys by the Lalauries, bystanders broke down the doors to the slave quarters and found "seven slaves, more or less horribly mutilated ... suspended by the neck, with their limbs apparently stretched and torn from one extremity to the other", who claimed to have been imprisoned there for some months.

One of those who entered the premises was Judge Jean-Francois Canonge, who when deposed claimed to have found in the Lalaurie mansion, among others, a "negress ... wearing an iron collar" and "an old negro woman who had received a very deep wound on her head too weak to be able to walk." Canonge said that when he questioned Madame Lalaurie's husband about the slaves, he was told in an insolent manner that "some people had better stay at home rather than come to others' houses to dictate laws and meddle with other people's business."

A version of this story circulating in 1836, recounted by Martineau, added that the slaves were emaciated, showed signs of being flayed with a whip, were bound in restrictive postures, and wore spiked iron collars which kept their heads fixed painfully in place.

When the discovery of the abused slaves became widely known, a mob of citizens attacked the Lalaurie residence and "demolished and destroyed everything upon which they could lay their hands". A sheriff and his officers were called in to break up the crowd, but by the time the mob left, the Royal Street property had sustained major damage, with "scarcely any thing [undamaged] but the walls." The slaves were moved to a local jail, where they were available for public viewing. The New Orleans Bee reported that by April 12 up to 4,000 people had attended to view the slaves "to convince themselves of their sufferings."

The Pittsfield Sun, citing the New Orleans Advertiser and writing several weeks after the evacuation of Lalaurie's slave quarters, claimed that two of the slaves found in the Lalaurie mansion died soon after their rescue. It added:

"We understand ... that in digging the yard, bodies have been disinterred, and the condemned well having been uncovered, others, particularly that of a child, were found."

These claims were repeated by Martineau in her 1838 book Retrospect of Western Travel, where she placed the number of unearthed bodies at two, including the child. An extended excerpt from her book follows. It makes harrowing reading:

Madame Lalaurie escaped from the hands of her exasperated countrymen about five years ago. The remembrance or tradition of that day will always be fresh in New-Orleans. In England the story is little, if at all, known. I was requested on the spot not to publish it as exhibiting a fair specimen of slaveholding in New-Orleans, and no one could suppose it to be so; but it is a revelation of what may happen in a slaveholding country, and can happen nowhere else. Even on the mildest supposition that the case admits of, that Madame Lalaurie was insane, there remains the fact that the insanity could have taken such a direction, and perpetrated such deeds nowhere but in a slave country. There is, as everyone knows, a mutual jealousy between the French and American creoles [natives] in Louisiana. Till lately, the French creoles have carried everything their own way, from their superior numbers. I believe that even yet no American expects to get a verdict, on any evidence, from a jury of French creoles. Madame Lalaurie enjoyed a long impunity from this circumstance. She was a French creole, and her third husband, M. Lalaurie, was, I believe, a French-man. He was many years younger than his lady, and had nothing to do with the management of her property, so that he has been in no degree mixed up with her affairs and disgraces. It had been long observed that Madame Lalaurie’s slaves looked singularly haggard and wretched, except the coachman, whose appearance was sleek and comfortable enough. Two daughters by a former marriage, who lived with her, were also thought to be spiritless and unhappy looking. But the lady was so graceful and accomplished, so charming in her manners and so hospitable, that no one ventured openly to question her perfect goodness. If a murmur of doubt began among the Americans, the French resented it. If the French had occasional suspicions, they concealed them for the credit of their faction. ”She was very pleasant to whites,” I was told, and sometimes to blacks, but so broadly so as to excite suspicions of hypocrisy.

When she had a dinner-party at home, she would hand the remains of her glass of wine to the emaciated negro behind her chair, with a smooth audible whisper, ”Here, my friend, take this; it will do you good.” At length rumors spread which induced a friend of mine, an eminent lawyer, to send her a hint about the law which ordains that slaves who can be proved to have been cruelly treated shall be taken from the owner, and sold in the market for the benefit of the State. My friend, being of the American party, did not appear in the matter himself, but sent a young French creole, who was studying law with him. The young man returned full of indignation against all who could suspect this amiable woman of doing anything wrong. He was confident that she could not harm a fly, or give pain to any human being. Soon after this a lady, living in a house which joined the premises of Madame Lalaurie, was going up stairs, when she heard a piercing shriek from the next courtyard. She looked out, and saw a little negro girl, apparently about eight years old, flying across the yard towards the house, and Madame Lalaurie pursuing her, cowhide in hand. The lady saw the poor child run from story to story, her mistress following, till both came out upon the top of the house. Seeing the child about to spring over, the witness put her hands before her eyes; but she heard the fall, and saw the child taken up, her body bending and limbs hanging as if every bone was broken. The lady watched for many hours, and at night she saw the body brought out, a shallow hole dug by torchlight in the corner of the yard, and the corpse covered over. No secret was made of what had been seen. Inquiry was instituted, and illegal cruelty proved in the case of nine slaves, who were forfeited according to law. It afterward came out that this woman induced some family connections of her own to purchase these slaves, and sell them again to her, conveying them back to her premises in the night. She must have desired to have them for purposes of torture, for she could not let them be seen in a neighborhood where they were known. During all this time she does not appear to have lost caste, though it appears that she beat her daughters as often as they attempted in her absence to convey food to her miserable victims. She always knew of such attempts by means of the sleek coachman, who was her spy. It was necessary to have a spy, to preserve her life from the vengeance of her household; so she pampered this obsequious negro, and at length owed her escape to him.

She kept her cook chained within eight yards of the fire place, where sumptuous dinners were cooked in the most sultry season. It is a pity that some of the admiring guests whom she assembled round her hospitable table could not see through the floor, and be made aware at what a cost they were entertained. One morning the cook declared that they had better all be burned together than lead such a life, and she set the house on fire. The alarm spread over the city; the gallant French Creoles all ran to the aid of their accomplished friend, and the fire was presently extinguished. Many, whose curiosity had been roused about the domestic proceedings of the lady, seized the opportunity of entering those parts of the premises from which the whole world had been hitherto carefully excluded. They perceived that, as often as they approached a particular outhouse, the lady became excessively uneasy lest some property in an opposite direction should be burned. When the fire was extinguished, they made bold to break open this outhouse. A horrible sight met their eyes. Of the nine slaves, the skeletons of two were afterward found poked into the ground; the other seven could scarcely be recognized as human. Their faces had the wildness of famine, and their bones were coming through the skin. They were chained and tied in constrained postures, some on their knees, some with their hands above their heads. They had iron collars with spikes which kept their heads in one position. The cowhide, stiff with blood, hung against the wall; and there was a stepladder on which this fiend stood while flogging her victims, in order to lay on the lashes with more effect. Every morning, it was her first employment after breakfast to lock herself in with her captives, and flog them till her strength failed. Amid shouts and groans, the sufferers were brought out into the air and light. Food was given them with too much haste, for two of them died in the course of the day. The rest, maimed and helpless, are pensioners of the city.

The rage of the crowd, especially of the French creoles, was excessive. The lady shut herself up in the house with her trembling daughters, while the street was filled from end to end with a yelling crowd of gentlemen. She consulted her coachman as to what she had best do. He advised that she should have her coach to the door after dinner, and appear to go forth for her afternoon drive, as usual, escaping or returning, according to the aspect of affairs. It is not told whether she ate her dinner that day, or prevailed on her remaining slaves to wait upon her. The carriage appeared at the door, she was ready, and stepped into it. Her assurance seems to have paralyzed the crowd. The moment the door was shut they appeared to repent having allowed her to enter, and they tried to upset the carriage, to hold the horses, to make a snatch at the lady. But the coachman laid about him with his whip, made the horses plunge, and drove off. He took the road to the lake, where he could not be intercepted, as it winds through the swamp. He outstripped the crowd, galloped to the lake, bribed the master of a schooner which was lying there to put off instantly with the lady to Mobile. She escaped to France, and took up her abode in Paris under a feigned name, but not for long. Late one evening a party of gentlemen called on her, and told her she was Madame Lalaurie, and that she had better be off. She fled that night, and is supposed to be now skulking about in some French province under a false name. The New Orleans mob met the carriage returning from the lake. What became of the coachman I do not know. The carriage was broken to pieces and thrown into the swamp, and the horses stabbed and left dead upon the road. The house was gutted, the two poor girls having just time to escape from a window. They are now living, in great poverty, in one of the faubourgs. The piano, tables, and chairs were burned before the house. The feather-beds were ripped up, and the feathers emptied into the street, where they afforded a delicate footing for some days. The house stands, and is meant to stand, in its ruined state. It was the strange sight of its gaping windows and empty walls, in the midst of a busy street, which excited my wonder, and was the cause of my being told the story the first time. I gathered other particulars afterward from eyewitnesses.

Delphine Lalaurie's life after the 1834 fire is poorly documented. Martineau wrote in 1838 that Lalaurie fled New Orleans during the mob violence that followed the fire, taking a coach to the waterfront and traveling, by schooner, from there to Mobile, Alabama and then to Paris. Certainly by the time Martineau personally visited the Royal Street mansion in 1836, it was still unoccupied and badly damaged, with "gaping windows and empty walls".

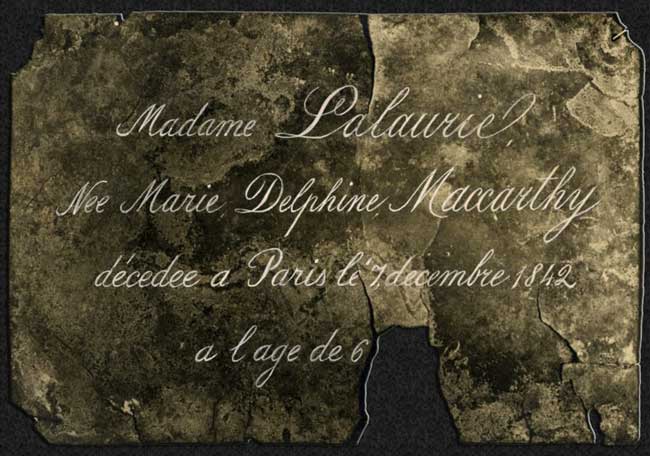

The circumstances of Delphine Lalaurie's death are also obscure. George Washington Cable recounted in 1888 a popular but unverified story that Lalaurie had died in France, in a boar-hunting accident. In the late 1930s, Eugene Backes, who served as sexton to St. Louis Cemetery #1 until 1924, discovered an old cracked, copper plate in Alley 4 of the cemetery. Its inscription read "Madame Lalaurie, née Marie Delphine Maccarthy, décédée à Paris, le 7 Décembre, 1842, à l'âge de 6--." A rough English translation for this is: "Madame Lalaurie, born Marie Delphine Mccarthy, died in Paris, December 7, 1842, at the age of 6-- "

According to the French archives of Paris, however, Marie Delphine Maccarthy died on December 7, 1849, at the age of 62.

The New Orleans house occupied by Delphine Lalaurie at the time of the 1834 fires stands today at 1140 Royal Street, on the corner of Royal Street and Governor Nicholls Street (formerly known as Hospital Street). At three stories high, it was described in 1928 as "the highest building for squares around", with the result that "from the cupola on the roof one may look out over the Vieux Carré and see the Mississippi in its crescent before Jackson Square".

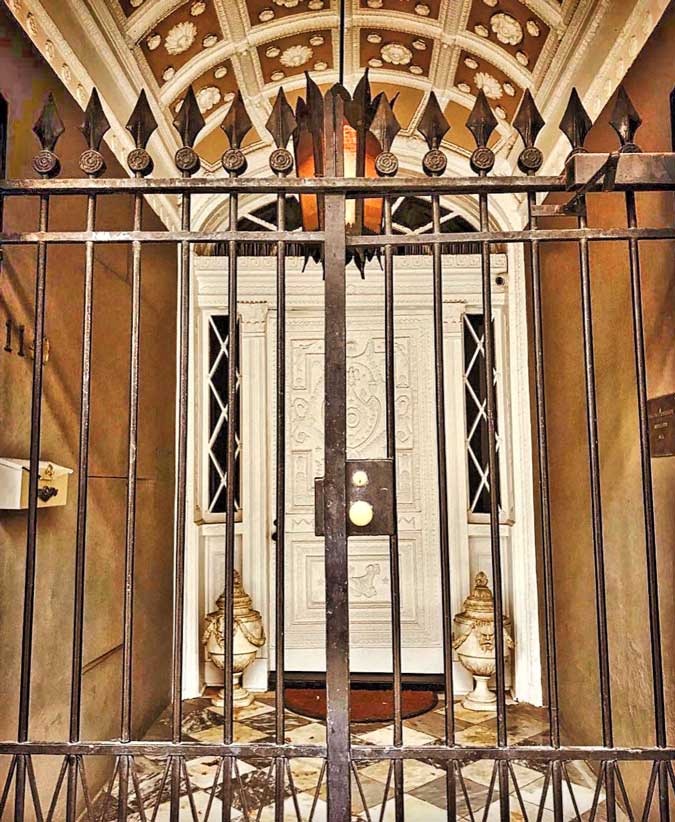

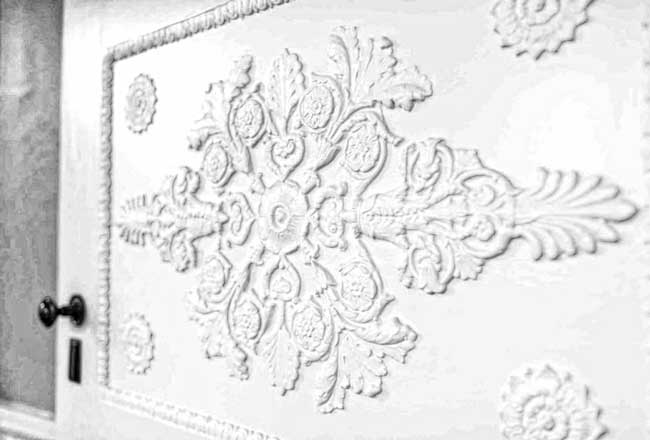

The entrance to the building bears iron grillwork, and the door is carved with an image of "Phoebus in his chariot, and with wreaths of flowers and depending garlands in bas-relief".

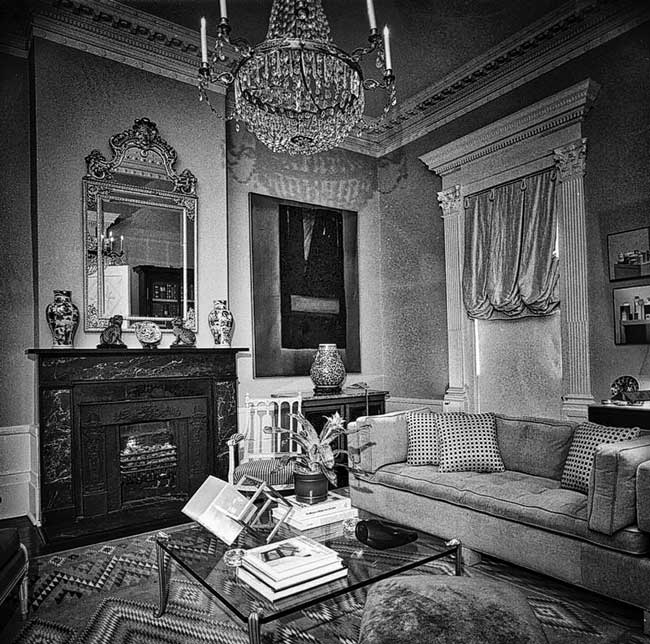

Inside, the vestibule is floored in black and white marble, and a curved mahogany-railed staircase runs the full three stories of the building. The second floor holds three large drawing rooms connected by ornamented sliding doors, whose walls are decorated with plaster rosettes, carved woodwork, black marble mantle pieces and fluted pilasters.

Subsequent to Lalaurie's departure from America, the house was left unchanged at least until 1836. But it was purchased and, at some point prior to 1888, it was restored. Over the following decades, it was used as a public high school, a conservatory of music, an apartment building, a refuge for young delinquents, a bar, a furniture store, and a luxury apartment building.

In April 2007, actor Nicolas Cage bought the Lalaurie House for a sum of $3.45 million. To protect the actor's privacy, the mortgage documents were arranged in such a way that Cage's name did not appear on them. On November 13, 2009, the property, then valued at $3.5 million, was listed for auction as a result of bank foreclosure and purchased by Regions Financial Corporation for $2.3 million.

In 2010 the mansion received a badly-needed makeover which both transforms it yet pays homage to its haunted past:

Folk histories of Lalaurie's abuse and murder of her slaves circulated in Louisiana during the nineteenth century, and were reprinted in collections of stories by Henry Castellanos and George Washington Cable. Cable's account (not to be confused with his unrelated 1881 novel Madame Delphine) was based on contemporary reports in newspapers such as the New Orleans Bee and the Advertiser, and upon Martineau's 1838 account, Retrospect of Western Travel. He added some of his own synthesis, dialogue, and speculation.

After 1945, accounts of the Lalaurie slaves became more gruesome and explicit. Jeanne deLavigne, writing in Ghost Stories of Old New Orleans (1946), alleged that Lalaurie had a "sadistic appetite [that] seemed never appeased until she had inflicted on one or more of her black servitors some hideous form of torture" and claimed that those who responded to the 1834 fire had found "male slaves, stark naked, chained to the wall, their eyes gouged out, their fingernails pulled off by the roots; others had their joints skinned and festering, great holes in their buttocks where the flesh had been sliced away, their ears hanging by shreds, their lips sewn together ... Intestines were pulled out and knotted around naked waists. There were holes in skulls, where a rough stick had been inserted to stir the brains." DeLavigne did not cite any sources for these claims, and they were not supported by the primary sources.

The story was further embellished in Journey Into Darkness: Ghosts and Vampires of New Orleans (1998) by Kalila Katherina Smith, the operator of a New Orleans ghost tour business. Smith's book added several more explicit details to the discoveries allegedly made by rescuers during the 1834 fire, including a "victim obviously had her arms amputated and her skin peeled off in a circular pattern, making her look like a human caterpillar," and another who had had her limbs broken and reset "at odd angles so she resembled a human crab". Many of the new details in Smith's book were unsourced, while others were not supported by the sources given.

Today, modern re-tellings of the Lalaurie legend often use deLavigne and Smith's versions of the tale as the basis for claims of explicit tortures, and number the slaves who died under Lalaurie's care at as many as one hundred.